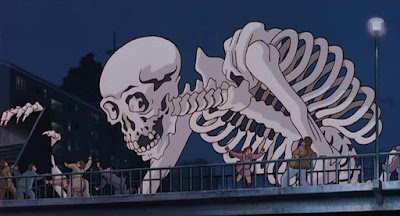

Howl from Beyond the Fog (2019) In this 35-minute short film from writer/director Daisuke Sato (effects crew, Godzilla: Final Wars, The Great Yokai War), set in the late 19th century, a village lake is guarded by a legendary creature. When a young blind woman and her family are threatened by greedy land developers, the fearsome kaiju (which is also blind) becomes her only salvation. The enchanting tale is depicted through puppetry, subdued light and acute camera angles to depict a monster of vast scale. Sato’s less-is-more approach creates a unique visual experience. My only quibble is that I wish the film were longer, leading me to hope the filmmaker makes a full-length feature someday.

Special thanks to the late Twitter user Freddie Premo (RIP) for recommending this to me a couple of years ago.

Rating: ****.

Available on Blu-ray, DVD, Prime Video and Tubi

The Secret of the Telegian (aka: Densô ningen) (1960) In this sci-fi movie with noir overtones, a group of businessmen are being murdered one-by-one, while the assailant is nowhere to be found. Clues point to a former soldier who vowed revenge against the officers who smuggled gold in the waning days of World War II. With the help of a disabled scientist who developed a device to transport matter, he methodically carries out his plan to murder the wealthy profiteers. Jun Fukuda’s second directorial effort is well-paced and suitably creepy (thanks to some impressive effects by Eiji Tsuburaya). It’s a shame The Secret of the Telegian remains largely unknown outside of Japan (it never received a theatrical release in the U.S.), so it’s long overdue for re-discovery.

Rating: ***½. Available

on DVD (Region 2)

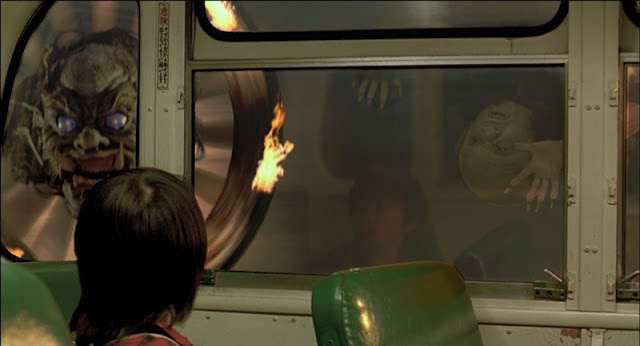

Bakemono (2023) A demonic creature, spurred on by a bitter middle-aged man (Takashi Irie) who made a pact with it, feeds off suppressed rage. Writer/director Doug Roos’ non-linear film, featuring a diverse Japanese/international cast, follows several guests over the course of a few nights, in a sketchy Tokyo Airbnb.The monster (or “bakemono” in Japanese) lurks in the shadows, pitting individuals against each other (and themselves). The delightfully icky practical effects (also by Roos) recall the work of Rob Bottin on The Thing. It’s a disconcerting, unnerving experience that requires your full attention, but well worth the time. Watch out for it.

Rating: ***½.

Available: Blu-ray (through Indiegogo), but watch for it elsewhere soon!

The iDol (2006) Ken (Jin Sasaki), a 20-something otaku who obsessively collects vintage space-age memorabilia, acquires a bright green action figure, which possesses hidden powers. In the span of a day, the fickle plastic toy arranges a dream date with his favorite celebrity, only to have him lose all his worldly possessions several hours later. Director/co-writer Norman England’s Twilight Zone-esque premise works well within the confines of the short film, although it would have been nice to see this expanded into a longer feature.

Rating: ***½. Available on Tubi

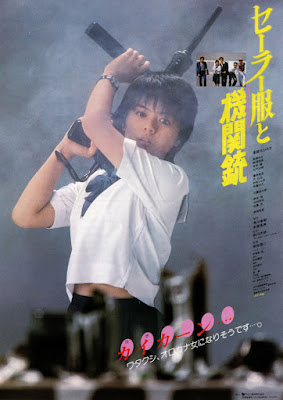

Sailor Suit and Machine Gun (1981) After her father’s sudden death, high school student Izumi Hoshi (Hiroko Yakushimaru) reluctantly becomes his successor as chairman of a small yakuza clan. As rival gangs close in to destroy them, she inadvertently discovers she has a knack for this kind of thing. Not your typical yakuza movie, Shinji Sômai’s sophomore effort is a winning combination of crime drama with social farce.

Rating: ***½.

Available on Blu-ray and Midnight Pulp

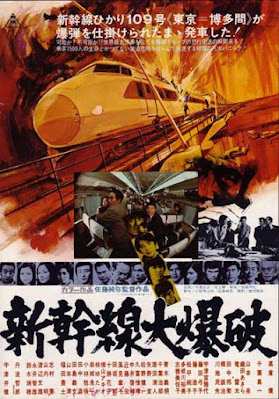

The Bullet Train (1975) Jun'ya Satô’s tense disaster thriller borrows a page from Airport (1970), starring Shin'ichi (“Sonny”) Chiba in the George Kennedy role, as Aoki, a determined rail employee. In the film’s premise (which, in turn, influenced the 1994 movie Speed), a bullet train carrying 1,500 passengers faces the grim prospect of exploding if it drops below 80 kph. Officials feverishly endeavor to find a way to locate and deactivate the bomb. At two-and-a-half hours, The Bullet Train is a bit overlong, but on the other hand, it devotes a commendable amount of screen time to establishing the bomber (Ken Takakura) and his co-conspirators as sympathetic, three-dimensional characters with believable motivations.

Rating: ***½.

Available on Blu-ray, DVD and Tubi

House of Terrors (1965) After her husband dies in a psychiatric hospital, a grieving widow discovers that she’s inherited a villa he secretly purchased. A stipulation of his will contends that she must share the property with his ethically ambiguous father (who was also his doctor at the time of his death). Most of the film, which recalls Italian gothic horror films of the period, takes place in a spooky old mansion with a creepy hunchbacked caretaker (Kō Nishimura). Although House of Terrors (aka: The Ghost of the Hunchback) borders on being a bit too derivative for its own good, it’s well worth a look for the gloomy atmosphere and pervasive eerie mood.

Rating: ***. Available on Blu-ray

Ghostroads: A Japanese Rock ‘n Roll Ghost Story (2017) Manabe Takashi stars as the leader of a mediocre retro rock band. He has a sudden burst of inspiration when he encounters the ghost of a blues musician in an old, battered amp, but soon learns that inspiration doesn’t come free. Faced with a Faustian bargain, he must choose between fame and his bandmates. Ghostroads features some fun music and unexpected cameos (watch for L.A. alternative music radio figurehead Rodney Bingenheimer), but Darrell Harris doesn’t really convince as a blues legend, and it misfires as a comedy. At a sparse 77 minutes, however, it won’t wear out its welcome… much.

Rating: **½.

Available on DVD (Region 2) and Tubi

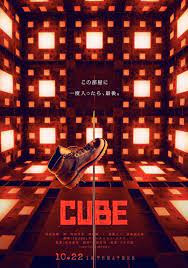

Cube (2021) Yasuhiko Shimizu’s remake of Vincenzo Natali’s mind-bending 1997 original about a group of strangers trapped in a vast multiroom structure adds a couple of interesting wrinkles to the original story, but otherwise doesn’t have anything new to say. Even the new booby traps seem uninspired. The characters are underdeveloped, and the drama over who lives and who dies seems more perfunctory than suspenseful. With no one to root for and few surprises, what was once novel is now repetitive and tedious.

Rating: **. Available

on Prime Video, Kanopy and Tubi