Diabolique (aka: Les diaboliques) (1954) Don’t be

surprised if you experience a distinct sense of déjà vu while watching Diabolique (The French pun is purely

unintentional). From a modern

perspective it’s easy to dismiss all of the plot twists and turns as clichéd, instead

of seeing them as the inspiration for so many modern psychological thrillers

(including Hitchcock’s Psycho and the

under-seen Hammer film Taste of Fear). Director Henri-Georges Clouzot’s film is a

skillful combination of suspense and superb acting. The characters includes Christina Delasalle (played

by the director’s wife Vera Clouzot) and Nicole Horner (Simone Signoret) as

wife and mistress, respectively, to Michel Delassalle (Paul Meurisse), a cruel

boarding school principal. Both women

conspire to murder Michel and end his tyrannical cycle of physical and mental

abuse. There’s a stark contrast between

Christina, who grapples with her belief system, and Nicole, who lost her faith

a long time ago. Just when they think

they’ve pulled off the perfect crime, Michel’s body goes missing. Even if the shocks are not quite as jarring

as they must have been for audiences in 1954, the film maintains a high level

of tension throughout. Often imitated,

but never duplicated, Diabolique is a

true masterpiece.

Rating: **** ½.

Available on DVD

The Big Heat (1953)

Fritz Lang directed this film noir gem set in Los Angeles. Glenn Ford plays Dave Bannion, an honest cop investigating

the suicide of a fellow police sergeant.

He discovers that there’s more to the story than he originally thought, tracing

a cycle of corruption that leads all the way to the top, but his superiors just

want to sweep everything under the rug. Lang

depicts a city ruled by fear, where everyone keeps their mouth shut if they

want to live another day, and no one wants to lend a helping hand for fear of

reprisal. As Bannion gets closer to the

answers, his wife gets caught in the crossfire.

He becomes an unstoppable force, intent on finding the men responsible

for her death, and taking down the crimelord who’s pulling all of the strings

in town. In addition to Ford’s superb

portrayal of a copy who’s been pushed too far, there’s some great supporting

performances by Lee Marvin as the icy hired thug Vince Stone and Gloria Grahame

as his wise-cracking girlfriend Debby. It’s

a tense, gritty and taut crime drama that’s not to be missed!

Rating: **** ½. Available on DVD

Four-Sided Triangle (1953) Few probably remember this obscure Hammer science fiction film

from director Terence Fisher, but it’s worth a look if you’re a Hammer

completist or B sci-fi enthusiast. The title

refers to the relationship between two scientists and the woman that they love,

and the unusual solution that one of them concocts to solve their dilemma. Bill (Stephen Murray) is a brilliant inventor

who creates a device that can duplicate anything (Don’t hurt your brain trying

to figure out how such a device could actually work – his extremely cursory

explanation might as well involve magic).

When his childhood friend Lena (Barbara Payton) marries his mutual

friend and colleague Robin, he does what any other sensible researcher would

do, and creates a copy of Lena (referred to as Helen). Other than being easy on the eyes, I’m not

really sure what all the fuss was about with Lena, considering the fact that

she didn’t know who Albert Einstein (No, really!) was, perhaps proving that

love is dumb as well as blind. Filled

with unnecessary narration and a contrived ending that sidesteps the headier

moral and ethical dilemmas raised throughout, Four Sided Triangle could

have been better, but it’s still quite watchable.

Rating: ***. Available on DVD

Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958) Nancy Fowler Archer (Allison Hayes) is wealthy, alcoholic and

emotionally unstable. Her philandering

husband Harry Archer (William Hudson) plots to have her committed to a mental

hospital so he can take control of her fortune and run off with local town

floozy Honey Parker (Yvette Vickers). Probably

no one would remember the film today if not for the stroke of insanity/genius

on the part of the producers, who decided to add a cheesy sci-fi twist to this

little melodrama. Nancy encounters an alien

ship (which is repeatedly referred to as a “satellite”) with a bald 30-foot

alien lurking inside. Apparently, he

wants her expensive diamond necklace because his ship runs on diamonds (Um,

okay), but she manages to evade him.

It’s never really explained how or why she grows to such enormous

proportions (or why the alien was 30 feet tall, and she’s supposedly 50 feet). Attack

of the 50 Foot Woman is so bad, it’s nearly good, and taken in the right

light can be a heck of a lot of fun. It

has terrible effects (the alien, his spacecraft, and the title character are

all transparent), hammy acting and characters no one cares about. It’s hard to imagine that anyone ever thought

this movie was a good idea, but I’m sort of glad that they went ahead with it

anyway. Nathan Juran (who was apparently

so embarrassed by the material that he went by the name “Nathan Hertz” for this

film), coincidentally directed the superlative fantasy The 7thVoyage of Sinbad the same year!

Rating: ** ½. Available on DVD

The Manster (aka: The Split) (1959) This bizarre Japanese/American

co-production might be worth a look just for its sheer audacity. American reporter Larry Stanford (Peter

Dyneley) is having a great time in Japan, while his co-dependent wife pines for

him in the States. He’s investigating a

mad scientist (played by Tetsu Nakamura) who performs strange, poorly defined

experiments on humans. Larry soon

becomes the newest subject of his research after he’s injected with the latest

batch of serum. As the serum takes

effect he begins to sprout a new noggin, and serves as living evidence that two

heads are not necessarily better than one. While the film itself is goofy fun, it’s

hampered by a completely unsympathetic main character. Larry is such a selfish jerk to begin with,

that it’s hard to care what happens to him when he turns homicidal and begins

to go on a killing rampage through the streets of Tokyo. Because he doesn’t really seem to possess a

good half, the film becomes a Mr. Hyde and Mr. Hyde story. The

Manster is chock full of hammy acting, ridiculous dialogue and an ending so

abrupt that you’d swear they chopped off a complete scene (and with a scant 72

minute running time, it’s a distinct possibility). This isn’t a good movie by any stretch of the

imagination, but if you’re in the right mood (or possibly inebriated) this

could just be the ticket.

Rating: ** ½.

Available on DVD and Netflix Streaming

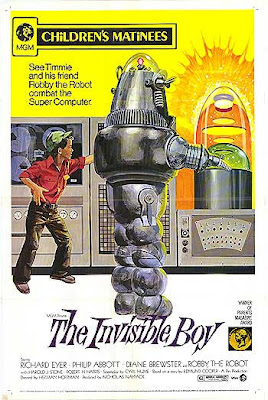

The Invisible Boy (1957) I regret to report that The Invisible Boy was not quite the lost

classic I was hoping for. With Robby the

Robot featured in a prominent role and a screenplay by Cyril Hume (who wrote

the screenplay for Forbidden Planet),

my level of expectations was set unrealistically high. While the film is sporadically amusing, it

eventually wears out its welcome due to an inconsistent tone and a meandering

story that seems to be cobbled together from other sci-fi movies. Richard Eyer stars as Timmie Merrinoe, providing

what I suppose is a “child’s eye” perspective of the world. His neglectful father (Philip Abbot) creates

a warehouse-sized supercomputer that runs off of punch cards (Ahh, modern

technology!), and fails to notice when his son successfully reassembles a robot

that was lying in pieces in his workshop.

Eventually, the computer becomes smarter, and takes control of Robby,

using the robot as an instrument to threaten the world. This odd shift in tone takes place about

two-thirds of the way in, as the film changes suddenly from whimsical to

serious. The stakes are raised as the

computer threatens to give the boy a slow, painful death (via Robby) if his

father doesn’t give in to its demands.

This isn’t exactly lightweight stuff, even if the movie itself is

supposed to be a slight “family” film.

The parents’ behavior is noticeably strange as well, as they appear to

be oblivious to Robby’s presence and mostly ignore Timmie. In one scene, the father is more interested in

doling out punishment than curious about how Timmy managed to become invisible. The

Invisible Boy is unavailable as a standalone disc, but can be found as an

extra (!) on the Forbidden Planet DVD

and Blu-ray. Come to think of it, you’re

probably better off just watching Forbidden

Planet instead.

Rating: **. Available

on DVD and Blu-ray (as an extra feature on the Forbidden Planet disc)