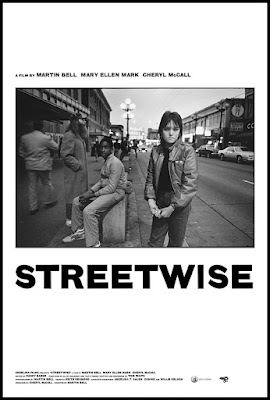

(1984) Directed by Martin Bell; Starring: Erin (“Tiny”)

Blackwell, “Rat,” DeWayne Pomeroy, Lou Ellen “Lulu”

Couch, Patrice Pitts, Kimberly Marsh; Available on Blu-ray

and DVD

Rating: ****

“The idea was to enter the world of these kids, to figure out the relationships between each other, and also between them and their parents – the ones that occasionally kind of visited their parents…” – Martin Bell (from 2021 Criterion commentary)

Years before I moved to the Seattle area, the Emerald City had captured my imagination and awe. Nestled along Puget Sound, with the Olympic Peninsula to the west, and the Cascades to the east, it possesses its own unique charm, melding a modern metropolis with breathtaking natural scenery. Perhaps because of its fortuitous location, or its rugged individualistic spirit, Seattle has long held its reputation (deserved and undeserved) as one of the most “livable” cities in the U.S. Beneath its glossy postcard exterior, however, another story was begging to be told.* Literally around the corner from one of the city’s most famous tourist attractions, the Pike Place Market, there is a parallel world that most people choose to ignore. Shot over a period of 55 days by director Martin Bell and his crew, Streetwise is an unflinching look at life on the street in downtown Seattle for several teenagers.

* Fun Fact: Streetwise was based on the Life magazine

story, “Streets of the Lost,” by Mary Ellen Mark and Cheryl McCall, who

collaborated with Bell for the film.

14-year-old Erin Blackwell, better known as “Tiny,” emerges

as the film’s nominal star. It’s difficult to hear her describe her work as a

prostitute, followed by a scene where she accepts a ride with an elderly client.

Sadly, we get the impression this isn’t something anomalous, but a typical day

in her life. Unlike many of the other kids in the film, her mother Pat (who

works as a waitress at a greasy spoon), is still in her life. Tiny comes home

intermittently, where she shares a contentious, chaotic relationship with Pat.

Watching the two interact, it’s easy to confuse who’s the grownup and who’s the

parent. The most horrifying aspect is her mother’s frank admission that she

doesn’t disapprove of her source of income. Indeed, she seems genuinely impressed

by her daughter’s claim that she made $200 in one day. Pat simply shrugs it

off, saying, “It’s just a phase she’s going through right now.” In another scene,

when Tiny attempts to speak with her mother, Pat curtly replies, “Don’t bug me,

I’m drinking.” While the street becomes Tiny’s maladaptive escape, booze is Pat’s

primary mode of detachment, at the expense of her daughter. It’s clear that Tiny

seeks attachment and stability in her life, but she’s trapped in a vicious cycle,

typified by neglect and loneliness. She speaks about wanting to have a baby,

but for now her little dog serves as a surrogate.

“Rat,”* a 14-year-old boy, subsists on the day-to-day grind of hustling pedestrians for spare change. He lives in an abandoned building with “Jack,” a 20-something drifter, who’s the closest thing to an authority figure. From Jack, he learns to subsist from eating out of dumpsters, and riding the trains. While lacking formal education, he possesses an innate intelligence, seeming to intuitively know how to work every angle. In one of his most clever scams, which he demonstrates for the camera, he orders a pizza at a restaurant, pretending the phone booth he’s calling from is his home address. When no one claims the pizza, they discard it in the dumpster, and he retrieves it. When he describes his estrangement from his parents (who live in Sacramento) it’s apparent that he doesn’t like being attached to anyone or anything for too long. He forms a brief bond with Tiny, but their relationship is doomed from the start.

* Fun Fact #1: the memorable opening scene where Rat jumps

off of a tall bridge into a river, 200 feet below, wasn’t shot in Seattle, but

in his home town of Sacramento, California, on the Rainbow Bridge (as a

re-enactment).

One of Streetwise’s most tragic stories belongs to 16-year-old DeWayne Pomeroy. Small for his age and malnourished (as a visit to a local free clinic confirms), he’s forced to live on the streets when his father Lemar is incarcerated for an arson conviction* Meanwhile, his mother is out of the picture. When he visits Lemar in prison, his father plays the part of the concerned parent, fearing that his son is going to end up like him. With limited options remaining for DeWayne, and nowhere left to turn, his future remains hazy.

* Fun Fact #2: According to Bell, Lemar was charged with

arson after burning an ice cream truck.

Several other young people, while lacking in overall screen time, make a big impression.* Lou Ellen Couch (aka, “Lulu”)** serves as a fearless protector for many of the younger, more vulnerable kids on the street. Because of her appearance and sexual orientation, she’s often a target for derision, but she doesn’t let the scorn of her detractors deter her from helping others. Patrice Pitts is full of swagger as a would-be pimp, and small-time hustler (in one amusing scene, he confronts a street preacher, questioning his intentions). When his mother and grandmother pay him a visit in a parking lot, the façade of alpha male posturing melts away, and we see him regress before our eyes. Fast-talking Kim (whom Bell described as “volatile”), puts on a hardened false front, estranged from her adoptive family, but we see the desperation set in as she arranges “dates” with anonymous male clients.

* Not-So-Fun-Fact: One of the teenagers briefly featured in the film is Roberta Hayes, who was murdered by Gary Ridgway (better known as the “Green River Killer”).

** Fun Fact #3: The film’s title comes from a line spoken by

Lulu, who sagely opines that to live on the street, you have to be “streetwise

like a motherf***er.”

Considering the deplorable situations the youths in Streetwise

endure, the obvious question is where does objective detachment end for the

filmmakers, and why didn’t they attempt to intervene at some point? The answer is

complicated, fraught with ethical gray areas. In order to get the stories and

images in his film, Bell and his crew gained unprecedented access to the young

people and their tumultuous lives, which required earning the confidence of

their subjects. Bell’s explanation was that “it was their life,” and he didn’t

want to put them in greater danger. Unfortunately, the story of these kids isn’t

unique to Seattle, but prevalent in every major city. It’s an uphill struggle, fighting

poor nutrition, inadequate (or no) healthcare, and the omnipresent hazards of

living on the street. The only conclusion is that the system has failed them. When

one of the teens prominently featured in the movie died by suicide while in

custody at juvenile hall, the film crew (in the process of editing the film) flew

back for the funeral, providing a poignant, all-too-familiar conclusion. The

death is another terrible statistic, a casualty of life on the street, and another

individual with potential, snuffed out long before his time. Streetwise

is a heartbreaking, unforgettable collection of stories, which will stick with

you long after the film has ended.