(1986) Written by Brian Trenchard-Smith; Written by Peter

Smalley; Based on the story “Crabs,” by Peter Carey; Starring: Ned Manning, Natalie McCurry, Peter Whitford and Wilbur Wilde;

Available on Blu-ray and DVD

Rating: ***½

“I have a motto: If in doubt, blow it up, or at least set

fire to it.” – Brian Trenchard-Smith (from the Arrow Blu-ray commentary)

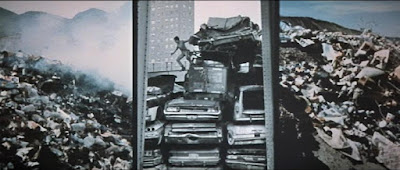

Many filmmakers have celebrated the drive-in movie theater and

the car culture that surrounds it, but it took director Brian Trenchard-Smith

to transplant these elements into his dystopian action film, Dead End Drive-In. This adaptation of Peter

Carey’s 1972 short story “Crabs,” (written for the screen by Peter Smalley), has

been described by Trenchard-Smith as “part

Mad Max, part Exterminating Angel.”

What’s a distinctly American invention doing in an Ozploitation* flick? While the

concept never caught on in most places around the globe, Canada and Australia**

are notable exceptions. The film was largely shot in Sydney’s last standing

drive-in on a budget of $2.3 million (presumably Australian dollars).

* Fun Fact #1: According to Trenchard-Smith, American

distributor New World Pictures wanted to dub the film with American accents, as

had been done with Mad Max (1979), but wisely decided against it.

** Fun Fact #2: According to DriveInMovie.com, the U.S. leads

the pack with more than 300 surviving drive-ins, 40 in Canada and 16 in

Australia.

Dead End Drive-In

hovers in the gray area between post-apocalyptic and dystopian movies, depicting

conditions that have grown progressively worse. Although not quite at the point

of civilization crumbling, it’s well on the way. After a global economic crisis,

prevailing conditions have forced governments to take drastic measures to

safeguard what’s left. In the opening scenes, we get a taste for everyday life

in the changed world. When we’re initially introduced to our protagonist Jimmy,

known as “Crabs” (Ned Manning),* he’s running for his life against a roving gang

of thugs. His brother works as a tow truck driver, picking up wrecks and

fighting off ruthless scavengers for auto parts. Crabs takes a break from his less than idyllic

life, bringing his girlfriend Carmen (Natalie McCurry) on a date to the Star Drive-In

in his brother’s prized ’56 Chevy (you can probably guess it doesn’t remain in

mint condition for long). The young lovers are unaware that this evening’s diversion

is destined to be a one-way trip. After some hanky- panky in the Chevy’s back

seat, Crabs discovers two of his wheels have been stolen. When confronted, the

drive-in manager Thompson (Peter Whitford) feigns ignorance, but he’s in league

with the cops who took the wheels. We soon learn the Star Drive-In is part of

the government’s solution for containing society’s undesirables: the homeless, aimless

youth, and eventually a group of immigrants. The restless detainees live out of

their vehicles, forming enclaves, watching movies all night,** taking government-issued

drugs and eating junk food all day.

* Fun Fact #3: Ned Manning claimed to be 24 when he

auditioned for the role, but was actually 36 at the time.

** Fun Fact #4: The films shown at the drive-in are

conveniently from Trenchard-Smith’s filmography, including Turkey Shoot and The Man from Hong Kong. The director remarked that he endeavored to

synch the action on the drive-in screen with the action in the film.

As Crabs and Carmen bide their time in the drive-in

concentration camp, their relationship progressively deteriorates. While Crabs looks

for a way out and resists making friends with the local denizens, Carmen doesn’t

question their internment. Like many of the people who are stuck there, she’s content

to have someplace to sleep that isn’t on the street. Unfortunately, Carmen

proves she’s not much more than a pretty face when she reacts adversely to the

new arrivals, joining the mob mentality of anti-immigrant sentiment.

Dead End Drive-In works

on different levels, as a mindless action flick with the requisite amounts of guns,

mayhem and nudity demanded by the genre, but it diverges from similar fare with

an exploration of the darker side of human nature. Aside from the conspicuously

‘80s fashion and music (supposedly depicting the mid-90s), the movie’s themes

hold up now. Anyone paying attention to today’s headlines will see much in

common with the events in the film, when a group of Asian immigrants are brought

into the drive-in community. Bigotry rears its ugly head, as they’re met with

suspicion and hatred, becoming the scapegoats for everything that’s wrong in

the drive-in (with the white troublemakers conveniently ignoring the fact that

it was a terrible situation before the immigrants ever arrived). In his

commentary, Trenchard-Smith pointed out the intentional parallels to Australia’s

recent history with Vietnamese immigrants (the “White Australia Committee” at

the drive-in mirrors the racist White Australia Policy from the early 1900s). He

commented that the Australian distributors didn’t like the inclusion of the

Asian immigrant subplot, because the controversy hit a little too close to home.

It was a message the older folks didn’t appreciate, but the youth understood. This

segment of the film only serves to illustrate how the terrible cycle repeats.

Change the location and the ethnicity, and the same irrational fears and tired

rhetoric follow.

There’s a point in the third act of many films where the

situation escalates, raising the stakes for its characters. Depending on the

skill of the filmmakers, the audience chooses to go with it or not. In the case

of Dead End Drive-In, Trenchard-Smith

injects a dose of social commentary into the action, distinguishing it from

being simply another dumb youth in jeopardy movie. We never see the outcome to

the drive-in’s impending race war, but it’s not too difficult to speculate how

it might end. Similarly, Crabs’ fate is open-ended because it has to be. As he embarks

on an uncertain future, it’s left to us to decide what sort of world we want to

inherit. Are we going down the dark path to social inequality or can we

overlook our differences and finger-pointing to arrive at mutually acceptable solutions?

Dead End Drive-In achieves a balance between

schlock and thoughtfulness without ever seeming preachy. If you like crazy

stunts (including a truck making a 160-foot jump through a sign) along with an

extended metaphor of the drive-in as a microcosm of society, then you’re in

luck. Not bad for a simple exploitation flick with guns, boobs and car crashes.