(1973) Directed by Richard Fleischer; Written by Stanley R.

Greenberg; Based on the novel Make Room!

Make Room! by Harry Harrison; Starring: Charlton Heston, Edward G.

Robinson, Joseph Cotten, Leigh Taylor-Young, Chuck Connors and Brock Peters; Available

on DVD.

Rating: ****

“The relevancy of the picture today stands up very strongly

against what is happening. This picture is usually listed under science

fiction, but as far as I’m concerned, the fiction part isn’t valid anymore.

This isn’t even a science picture, but we’re much closer to it than we realize

or want to be.” – Richard Fleischer (from DVD commentary)

You asked for it, you got it. Thanks to a recent Twitter

poll, the film du jour for Dystopian December is the one and only Soylent Green. I wouldn’t need much

prompting, however, to discuss one of the landmark science fiction films of the

1970s, directed by the underrated Richard Fleischer. Not enough credit is given

to Fleischer for his exemplary contributions to genre filmmaking. With 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) and Fantastic Voyage (1966) under his belt,

he adopted a less fanciful approach to depict a planet in crisis. Stanley

Greenberg’s script, based loosely on Harry Harrison’s book Make Room, Make Room, explores the source material a step or two

further, taking the consequence of overcrowding to its logical, horrible conclusion.

Even if you’ve never watched Soylent Green, you’re probably aware of the more (ahem) unsavory

aspects of the plot. For the benefit of those who haven’t seen it, I’m taking

the middle ground, and will do my best to steer clear of any big spoilers. The

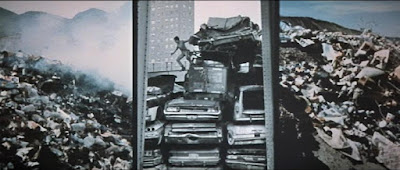

opening credits effectively set the tone for the rest of the film, with a

montage of still photos, which depict, beginning in the 1800s, a steady rise of

the population, linked with rise of the industrial revolution. Urban centers

become increasingly congested, and pollution, strife, rampant unemployment, poverty

and sickness follow. A caption informs us the population of New York City (the

movie’s setting) has skyrocketed to 40 million in 2022. The term “gritty” is overused, typically to describe a

reboot/reimagining, etc. of a movie, but in this case, it’s an appropriate

descriptor. The Earth has been irreversibly damaged by the greenhouse effect,

raising the temperature and making basic resources scarce. Society is in

decline and stagnation, literally and metaphorically feeding upon itself. Most

of the populace lives in crumbling buildings,* choked in a perpetual gauzy,

pollution-choked haze.** Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony (Symphony #6) figures

prominently in one of the film’s key scenes and end credits, a callback to a verdant

past that no longer exists.

* Fun Fact #1: according to Fleischer, this was the final

film to be shot on MGM’s backlot, before it was demolished. The ramshackle state

of the building facades only added to the film’s atmosphere.

** Fun Fact #2: Fleischer worked with cinematographer Richard

H. Kline to develop a filter, using water and green dye, to simulate the

polluted air of the street scenes.

Charlton Heston stars as detective Thorn, who works for a

corrupt police department where everyone’s on the take (His boss, Chief Hatcher

(Brock Peters), explains, “You’re bought as soon as they pay you a salary.”).

By virtue of having a job and a residence (he shares a dingy apartment with his

roommate Sol), he’s more fortunate than most. When he’s sent to investigate the

murder of a well-to-do corporate board member, he’s not above pilfering his luxury

apartment for a few niceties. Everyone gets a cut, from the clean-up crew to

his boss. Heston successfully walks the line between integrity and roguish behavior

with his character. Thorn’s just a survivor, like everyone else in this damaged

society.

Joseph Cotten leaves a lasting impression in his short role as

William Simonson, a lawyer on the board of the Soylent Corporation who learns a

terrible secret. He lives a sheltered life in a high-rise luxury apartment

building, isolated from the squalor of the city below. The weight of the secret

proves too much to bear, and someone decides his knowledge is too dangerous to

be kept. In a polite exchange with his assassin, Simonson, resigned to his fate,

concludes his death is inevitable, based on the dire circumstances. It’s not right

that he dies, but it’s an inevitable byproduct of the wheels that have been set

in motion.

Leigh Taylor-Young presents a tragic figure as Shirl, Simonson’s

former lover and semi-permanent resident of the apartment building (she and her

cohorts are referred to as “furniture”). She’s emblematic of the role of women

in this future society, as little more than servant and sex object, fit for

entertaining and odd chores. After Simonson’s demise, she’s worried about her

fate, and being accepted by the new tenant. For Shirl, there’s no escape from

her life of indentured servitude. She faces an uncertain future as she grows

older, which we can only speculate about.

The film’s most affecting performance belongs to Edward G. Robinson,*

in his celebrated 101st and final role (Robinson passed away a few

weeks after filming completed). He proves his versatility as Thorn’s roommate

and moral center, and serves as the heart of the film. As a former college

professor, he understands the value of books, knowledge and beauty, and laments

what has been lost. He’s lived too long and seen too much, remembering a time

when good food was plentiful and living conditions were more hospitable. Not

much is made of their living arrangement, or how they came to become roommates,

but they interact like an old married couple, cognizant of each other’s moods

and idiosyncrasies. There’s an unspoken love between them, best illustrated by an

endearing (mostly improvised) meal scene.

* Interesting Fact: According to Fleischer, Robinson was

almost completely deaf by the time he appeared in Soylent Green. Through meticulous

rehearsals and careful timing of his scenes, Robinson concealed his inability

to hear his fellow actors.

Food, and its scarcity, is one of the movie’s focal elements.

Even for the wealthy, fresh ingredients (fruit, vegetables and meat) are rare

and prohibitively expensive. Strict rationing is a way of life for the masses. Most

people subsist off government-issued processed food wafers of questionable nutrition:

Soylent Red, Yellow and Green,* pure sustenance, nothing more. When the supply

of Soylent is exhausted, resulting in a full-blown riot, Thorn and his fellow

cops are called upon to keep the peace. Big trucks equipped with scoops help

collect and disperse any lingering members of the crowd. The trucks, and other waste

vehicles throughout the film reinforce a recurring theme, how most people are

regarded as little more than garbage.

* Fun Fact #3: If you ever wondered what Soylent Green

tasted like (And why would you?), according to Fleischer, the green crackers

were nothing more than pieces of wood painted green.

Soylent Green may

not be the flashiest science fiction film to come out of the 1970s, but it’s

among the most thought-provoking. The superb cast, including two golden age

actors, Robinson and Cotten, sell the dire circumstances of a world stretched

beyond the breaking point. Of the many dystopian movies, this one seems to

present the most plausible scenario. We’ve already seen many of the factors in

the movie come to fruition, with too many people and not enough resources, widespread

corruption, big corporations that are more interested in the bottom line, and

elected officials that are paid to look the other way. Sadly, Soylent Green becomes less fiction and

more fact with each passing year, a rumination on what could be, as well as a

reflection of what already is.

Your fun facts are one of the many things I enjoy about your reviews, Barry!

ReplyDeleteThanks, John! It's fun digging up the facts!

Delete