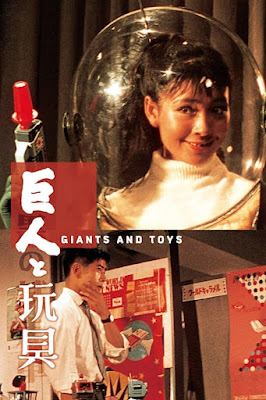

(1958) Directed by Yasuzô Masumura; Written by Yoshio Shirasaka; Based on the novel by Takeshi Kaikô; Starring: Hiroshi Kawaguchi, Hitomi Nozoe, Hideo Takamatsu, Michiko Ono; Available on Blu-ray and DVD

Rating: ****

“You’re behind the times. You don’t understand the age of

media. Listen, modern people are worse than babies. Worse than dogs. Why?

Because they don’t think. They work like slaves in the day, get drunk and play

pachinko at night. Or they listen to the radio, or watch TV. When do they have

time to think? Their heads are empty. That’s where we come in. We’ll hammer our

message into their heads over and over again, ‘Delicious caramel, World

Caramel. World, World, World!’ Then every time they see a pack, they’ll

automatically buy it. Do you get it now? We can control them with radio, TV and

movies. We can make the masses think and feel whatever we want. The media is

the dictator, the emperor of the modern age!” – Ryûji

Gôda (Hideo Takamatsu)

When most people think of the most significant and influential names in Japanese cinema, the usual suspects are bandied about. One overlooked filmmaker who merits more attention is Yasuzô Masumura.* Despite his prolific creative output throughout the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, many of his films (with a few notable exceptions) remain unseen in the West. Masumura established himself as a formidable creative force with his vicious satire, Giants and Toys (aka: Kyojin to Gangu), skewering Japan’s changing landscape in the realm of business, and as an emerging economic superpower.

* Fun Fact #1: Masumura’s educational background in Law, Literature

and Philosophy informed his unique vision. He further honed his craft, studying

film in Italy at the prestigious Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia.

Eager young college graduate Yôsuke Nishi (Hiroshi Kawaguchi) lands a publicity job for World Confectionary, which is embroiled in a fierce competition between rivals Giant Chocolate and Apollo Drops.* He wants to impress his boss Ryûji Gôda (Hideo Takamatsu) at any cost, which includes grooming a young, rough-around-the-edges woman to be the company’s new spokesmodel. Meanwhile, he takes a romantic interest in Masami Kurahashi (Michiko Ono), who works for Apollo, but his intentions are less than sincere. Likewise, Masami proves to be just as capricious as her boyfriend. Between whispering sweet nothings, they press each other for details about the latest marketing campaigns in their respective companies. The rivalry carries over to his friendship with college buddy Tadao Yokoyama (Kôichi Fujiyama), who shills confections for Giant.

* Fun Fact #2: In Takeshi Kaikô’s original story, the

company names were, respectively: Samson, Hercules, and Apollo.

At the age of 38, Gôda (Hideo Takamatsu) is an ambitious, upwardly mobile executive, who’s old before his time. He runs himself ragged, neglecting sleep in favor of his work, and popping pills to keep himself going. He neglects his wife Suzue (Hiroko Machida), the daughter of his superior, whom he married for strategic reasons, rather than matters of the heart. As his career continues its upward trajectory, his health spirals down to the point where he coughs up blood on his promotion letter. He purveys an ethos of success at any cost, which trickles down to his subordinate, Nishi.

Hitomi Nozoe plays the bubbly ingenue Kyôko Shima, who seems an unlikely poster girl for a candy company, with her rotten teeth. Her cute, unpolished exuberance catches the eye of Gôda, however, who sees her potential. Thus begins her Pygmalion-like transformation, as she quickly becomes an overnight celebrity. Along with her rapid ascension in the public’s consciousness, her entire tone changes, as she transitions from an amiable, unpretentious girl from the slums, to a self-absorbed, quasi-sophisticate. Nishi doesn’t buy her instant celebrity status, aware of the half-life of a fickle public and the ephemeral nature of fame. He tells Nozoe it’s only a matter of time before someone takes her place, but she’s self-aware, enjoying the ride while it lasts (“So what? I don’t mind being a puppet or a toy. As long as I’m having fun, that’s enough.”).

* Fun Fact #3: While their onscreen characters shared a

contentious relationship, co-stars Kawaguchi and Nozoe married in 1960.

Giants and Toys playfully equates modern business

to feudal Japan. One sequence hammers home the metaphor, with shots of the three

candy company banners waving high. Their employees go into battle, developing strategies

of attack and defense, with spies around every corner. When the main factory of

a rival company burns down, an older World executive calls for bushido, the ancient

samurai spirit of honor among adversaries. He’s summarily dismissed by his

colleagues as naïve and old fashioned. No one in the film is entirely trustworthy

or above compromising their integrity. Honesty only brings you so far, everyone

has an ulterior motive, and no one is above selling out. Lies, betrayal, and

subterfuge are simply part of the game. Gôda’s speech about how easily the

general public are manipulated is downright prophetic. Advertising is all about

creating a need for something that didn’t exist before, doing the thinking for

people. Choice is an illusion. Giants and Toys also takes a cynical

stance toward relationships in the context of the film, which appear solely

transactional in nature – rather than what you can do for someone else, it’s

about what you can get from them.

Cinematographer Hiroshi Murai’s candy-colored presentation is only appropriate for a story about rival confectionary companies. The garish, saturated colors underscore the exaggerated onscreen antics. Amidst the humor, Giants and Toys has a serious message about the new disposable culture. In Kyôko’s case, she’s nothing more than the flavor of the month, pre-packaged and rammed down the public’s collective throat, like the candy her company sells – sweet on the surface, and just as insubstantial. Cutthroat business tactics are an accepted fact. Masumura applied similar themes, adopting a darker tone with his Black Test Car (1962). Compared to the later film, Giants and Toys tells its story in broader, breezier strokes, making the themes more accessible (not to mention a lot more fun). With its breakneck pace and rapid-fire dialogue, Giants and Toys deserves to be re-discovered. The film’s strikingly contemporary commentary on fame, consumer culture and business remains as relevant today as it was in 1958, making this a true classic.

Sources for this article: Arrow Blu-ray commentary by Irene

González-López; “In the Realm of the Publicists,” video essay by Earl Jackson,

Jr.; Yasuzô Masumura biography on Fantomas Blind Beast DVD, by Earl

Jackson, Jr.

Terrific review, Barry!

ReplyDeleteGiants and toys sounds like a wickedly fun satire! I am curious if the garish colors almost make it hard to watch.

Thanks so much, John! It's a great transfer. Although the colors may be a big garish, they're never overwhelming. Such a fun movie.

DeleteWow, this sounds fantastic. Brilliant how much they seemed to have nailed contemporary culture. Hope one day to check it out.

ReplyDeleteYes, indeed! It's amazing how contemporary this movie seems. Thanks for stopping by! :)

DeleteThis looks fascinating. I've read about contemporary Japanese soul-searching after a decade or more of economic stagnation, but this stands out as a critique just as the Japanese producer/consumer powerhouse was starting to fire on all cylinders, and "work until you drop" was unquestioned as an ethos. I imagine this film didn't get the best reception at the time (?). Keep up the great work introducing us to these unique films!

ReplyDeleteThank you so much! This film is something special. It has a serious message, wrapped around a candy-colored shell. I understand that it wasn't a hit at the time, and critical reception overseas was decidedly mixed. It was certainly ahead of its time.

Deletelove to see the movie.

ReplyDeleteIt's well worth seeking out. Thanks for stopping by!

Delete