High and Low (aka:

Tengoku to Jigoku) (1963) High and Low is film noir Akira Kurosawa

style, employing many of the familiar tropes of the genre to explore the darker

side of success and fortune. Toshirô Mifune stars as wealthy shoe company

executive Kingo Gondo. On the eve of Gondo assuming ownership of the company,

his chauffeur’s son is kidnapped for ransom, and he must choose between his

livelihood and the life of the boy. The story takes its time to unfold, with

the first half confined to virtually one set, Gondo’s house, before taking us

outside its confines. The film’s Japanese title, Tengoku to Jigoku, meaning “Heaven and Hell,” aptly describes the

contrast between Gondo’s comfortable, sheltered existence on top of a hill,

contrasted by the realities of the slum below. We’re afforded time to

contemplate his lofty position, as well as the motivations and inner torment of

extortionist and victim. Memorable scenes include a jazzy night club, a seedy

back alley populated by heroin addicts, and a sequence that masterfully employs

a spot of color on an otherwise black and white film. In director/co-writer

Kurosawa’s riveting contemplation of crime, no one emerges unscathed or

victorious.

Rating: ****½. Available on Blu-ray and DVD

Detour (1945) Al

Roberts (Tom Neal), a drifter in a diner, recalls the chain of unfortunate events

that led to his peripatetic lifestyle. When his lounge singer girlfriend

(Claudia Drake) moves to Los Angeles to pursue her fame and fortune, he sets

out on the road after her. His hitchhiking journey becomes disastrous, however,

when he winds up with a dead driver. Instead of reporting the incident to the

cops, he takes the driver’s car, along with his money and identity. Things turn

from bad to worse after Roberts picks up another drifter, Vera (Ann Savage),

who’s wise to his transgressions. Savage steals the show with her vitriolic performance.

Director Edgar G. Ulmer (The Black Cat)

and writer Martin Goldsmith pack a lot into such a short span (the film clocks

in at only 68 minutes). It’s decidedly brisk, but never hurried. Roberts is

compelling as the unreliable narrator – we’re supposed to believe he’s innocent,

but as his life unravels, you’re never quite sure. The tacked on ending, an

obvious concession to the Production Code, brings a swift resolution to the

ambiguous climax. This is essential viewing for any fan of the genre.

Rating: ****. Available on DVD

Le Samouraï (1967)

Director/co-writer Jean-Pierre Melville’s post-modern film noir doesn’t get

hung up on a labyrinthine plot – it’s more about capturing a specific look and

feel. Set amidst the rain-soaked streets of Paris, the focus is on laconic hitman

Jef Costello (Alain Delon), who lives by his own code and embodies honor and

style in equal measures. After he’s held by the police, he attempts to track

down the former employers who now want him dead. With Costello, it’s the little

details that count, as in one scene where he trades a hat and coat with another

suspect, and carefully adjusts the brim of his fedora. Nathalie Delon is also

memorable as his close-mouthed girlfriend, and Cathy Rosier shines as the

piano-playing femme fatale, who witnesses Costello leaving the scene of a crime.

Melville paints a picture that turns film noir on its head, where the police

seem far less honorable than the criminal, and style is the substance.

Rating: ****. Available on Blu-ray and DVD

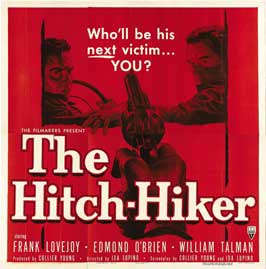

The Hitch-Hiker

(1953) Director/co-writer Ida Lupino’s thriller sustains an almost unbearably

tense atmosphere from start to finish. Two men (Edmond O'Brien and Frank Lovejoy)

on a fishing trip in Mexico experience an abrupt change in plans when they pick

up a murderous hitch hiker (William Talman). Talman is chilling as escaped

criminal Emmett Myers, who orders the men to assist him with his getaway. The

hijacked pals carefully plot against the sociopath, knowing they’re just a

means to an end, to be discarded when he’s done. One especially affecting scene,

set in a Mexican general store, affirms the friends’ humanity, while

reinforcing the antagonist’s barely restrained capacity for evil. Warning: because

this movie has fallen into the public domain, be sure to find a good quality

copy (The murky version I watched was more noir than film).

Rating: ***½. Available on Blu-ray and DVD

The Killing (1956) This stylish early film by Stanley

Kubrick wasn’t a favorite of the director’s, but there’s a lot to like about

it. Sterling Hayden (who would appear as Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper in Dr. Strangelove) stars as Johnny Clay,

the mastermind of a $2 million race track heist. It’s not too difficult to

imagine his menacing clown mask influencing the bank robbery scene in 2008’s The Dark Knight. Although the film is hampered

by extraneous narration (a choice Kubrick opposed), it features some outstanding

performances. Elisha Cook, Jr. is terrific as the big-talking, obsequious George

Peatty, and Marie Windsor is engaging as his two-timing wife, Sherry. Perhaps a

voiceover-less version will surface one day, allowing the audience to connect

the dots of the elaborate caper on our own.

Rating: ***½. Available on Blu-ray and DVD