Rating: ****½

“Ladies and gentlemen, Cesare the somnambulist will answer all your questions. Cesare knows every secret. Cesare knows the past and sees the future. Judge for yourselves. Don’t hold back, ask away!” –Dr. Caligari (Werner Krauss)

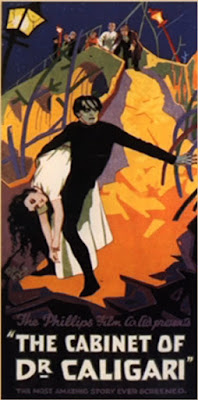

Modern horror films owe a debt of gratitude to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which has been encoded in the DNA of virtually every genre title that followed. Likewise, it’s a safe bet that Tim Burton’s movies wouldn’t have been the same without the influence of this landmark film and its distinctive visuals. I can’t substantiate how it must have also influenced the goth look, but we’ll just chalk it off to the collective unconscious (and dedicated fans of silent horror). Some of the most enduring films stem from Germany’s Weimar Era, a vibrant period for cinema, typified by a new generation of filmmakers who pushed the envelope visually and thematically. Director Robert Wiene’s* The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari ** made a big splash when it debuted in February 1920, with its mind-bending story and dream world made real.

* Fun Fact #1: Although some dispute the veracity of this claim, many assert that Fritz Lang was originally chosen to direct the film, but was otherwise occupied with the production of The Spiders (1919/1920).

** Fun Fact #2: In the early ‘30s, while in self-imposed exile

from Germany, Wiene planned to direct a sound remake of The Cabinet of Dr.

Caligari, starring Jean Cocteau as Cesare. Due to illness and the inability

to secure funding for the project, the remake never became a reality.

In the opening scene, set in an asylum for the mentally ill, Franzis (Friedrich Fehér) relates to a fellow patient how he came to be in his current predicament. Cut to the sleepy village of Holstenwall, where mesmerist Dr. Caligari petitions the town clerk (who sits in a cartoonishly tall chair) to display his novel attraction at the annual fair. The star of Caligari’s show is Cesare (Conrad Veidt), a somnambulist, who resides in a coffin-like wooden box (forget about the ethics of transporting a person like a piece of luggage). Supposedly gifted with clairvoyance, Cesare awakens only on his master’s command. Franzis convinces his lifelong friend (and rival for the affections of the comely Jane Olsen) Alan to indulge in frivolity and accompany him to the fair, where they stumble upon Caligari’s exhibit. A fun day out turns into a nightmare when Alan asks Cesare how long he’ll live, prompting the reply, “To the break of dawn.” Unfortunately for Alan, the prophecy proves to be true, as he’s later discovered, murdered in his bed. Under the direction of the diabolical Caligari, Cesare is commanded to obey his every whim, which includes eliminating anyone who displeases him. The town falls into a panic as the residents wonder who the next victim will be. Devastated by his friend’s violent death, and fearing for Jane’s (Lil Dagover) life, Franzis tasks himself with tracking down Caligari and bringing the mad doctor to justice. His search leads him to an insane asylum, where Caligari resides as the institution’s director. This discovery sends Franzis into a tailspin, as he (and the audience) questions his grip on reality.

The film’s aesthetic choices (courtesy of production designers Walter Reimann, Walter Röhrig and Hermann Warm), often cited as a prime example of German expressionism, depict a world comprised of impossible landscapes, skewed angles (what would the ‘60s Batman TV show be without this movie?), and ominous shadows. In a conscious effort to stray from realism, there isn’t a rectangular door or right angle in sight. Conrad Veit, as Cesare, with his tall, lanky frame, gaunt appearance, and skin-tight dark clothing, almost seems an extension of the architecture. He’s little more than an automaton, programmed to follow Caligari’s twisted whims.

Sigmund Freud opined that dreams were the “royal road to the unconscious.” The film is a waking nightmare, with its uniquely twisted version of reality. But within the artificial world of Caligari, we confront the darker impulses that lie within ourselves. Who, in our darkest moments, hasn’t had an intrusive thought about acting out something that would be otherwise unconscionable? If we had an agent to carry out our unsavory impulses, our hands, if not our conscience, would remain clean. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari also reflects our collective anxieties about losing our faculties to distinguish reality from fantasy. Who is the puppeteer and who’s the puppet master? Caligari pulls Cesare’s strings, but who manipulates Franzis? It’s revealed that the doctor isn’t the real Caligari, but an ardent student of his research. Amidst his own research he concludes, “You must become Caligari” (which also became the film’s advertising slogan) if he is to understand Caligari.

Much like the film’s overall visual aesthetic, the story is told in broad strokes, from the perspective of Franzis, an unreliable narrator. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari keeps us on edge from moment to moment, until we (like the characters in the film) can no longer trust our perceptions. Are we to take Franzis’ account at face value regarding the director of the asylum, or are his recollections merely the elaborate delusions of a disordered mind? Signs point to the latter, but the final shot of Caligari suggests otherwise. Either way, it’s a discombobulating experience, guiding us on the kind of uncanny journey that only horror can take us. Once watched, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is never forgotten – leaving an indelible mark after playing in the toybox of our minds.

Sources for this article: Beyond Caligari – The Films of

Robert Wiene, by Uli Jung and Walter Schatzberg; The Haunted Screen,

by Lotte H. Eisner; “Suggestion, Hypnosis, and Crime,” by Stefan Andriopoulos

(from Weimar Cinema, edited by Noah Isenberg); Caligari: How Horror

Came to the Cinema (2014 documentary)