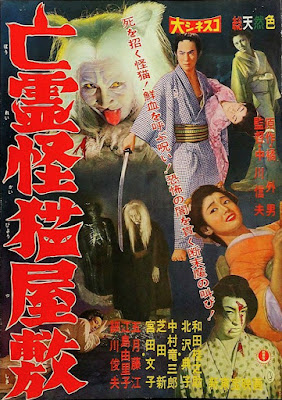

(1969) Directed by Yoshiyuki Kuroda and Kimiyoshi Yasuda; Written by Tetsurô Yoshida; Starring: Kôjirô Hongô, Pepe Hozumi, Masami Burukido, Mutsuhiro and Yoshindo Yamaji; Available on Blu-ray and DVD

Rating: ***½

“I’m the guardian of this place, the Onizuka. Those who do

not heed the warnings will be cursed by the Onizuka spirits and meet a swift

end. In addition, tonight is the night when once a year, not only will there be

the usual apparitions, but also the ones from deep in the mountains, and the

ones from the swamps will gather. There’s an old saying which states Onizuka is

a spiritual land, where apparitions from all over Japan gather, because it is

connected to the world where the apparitions live.” – Jinbei (Bokuzen Hidari)

It’s tough being third. If the second movie in a trilogy is bad, the next film might redeem the series. Conversely, the third movie in a trilogy could be (and frequently is) the weakest link. In this case, the bar was set impossibly high. The previous two films of the Daiei Film’s* Yōkai Monsters trilogy, 100 Monsters and Spook Warfare (aka: Big Monster War), were solid pieces of entertainment, featuring an almost encyclopedic listing of the quirky Japanese spirits. Compared to its predecessors, Along with Ghosts is decidedly lighter on the yōkai, but more character and plot-driven.

* Fun Fact: In Japan, Along with Ghosts appeared on a

double bill with Gamera vs. Guiron.

A group of Yakuza, led by their boss Higuruma (Yoshindo Yamaji) are waiting to ambush two samurai carrying an incriminating document (what’s precisely on the document is never made clear). Jinbei (Bokuzen Hidari), an old man, warns them that they’re on sacred ground, and any violence on their part will unleash a curse. In the tradition of cinema, where no one believes old men and ancient curses, the Yakuza thugs go about their dastardly plot, fatally wounding Jinbei when he steps in the way. His seven-year-old granddaughter, Miyo (Masami Burukido) happens to witness the event, and now she’s marked for death as a witness. Before he perishes, he instructs her to seek out her father, in the town of Lui, four leagues away.* Miyo sets off alone, while, meeting a helpful boy and a ronin (masterless samurai) named Hyakasuro (Kôjirô Hongô). Higuruma takes on the role of bodyguard, after he offers to accompany her on the way to Lui. The odds are against Miyo and Hyakasuro, with Higuruma’s thugs on their tail, but help comes in the form of vengeful yōkai with an axe to grind.

* Approximately 14 miles away.

Miyo and Hyakasuro’s endearing relationship provides a good argument for finding your own extended family. Hyakasuro is a kind and virtuous man, who will stop at nothing to protect her from harm. (SPOILER WARNING) We soon discover he provides a stark contrast to her real father, Sakiichi (Mutsuhiro), the capricious lapdog of the same Yakuza clan they’re evading. He’s ready to beat a confession out of Miyo until he discovers a pair of dice in her possession, proving that she’s his daughter. To make matters worse, in the previous scene, he suggested to the Yakuza that they could use her as a human shield against Hyakasuro. All seems well when Sakiichi eventually turns on his employers, reuniting him with his daughter, but letting the aforementioned slide requires more than a little cognitive dissonance on the viewer’s part.

While Along with Ghosts may not have the abundance of yōkai of the previous two films, they’re there, albeit in more ancillary roles. You’ll find Nopperabo (faceless spirits impersonating humans), the cyclopean Dorotabo, a Wanyudo (“Wheel Priest”), a Tsuchikorobi (another cyclops, resembling a huge hairy mound), and a Konaki-Jiji (masquerading as Miyo for a piggyback ride). If this had been the first, rather than the last, in the trilogy, it would be regarded as a nice preview of the movies that were to follow, whetting our appetites for all things yokai. But don’t sell this one short. Boasting an engaging storyline and distinct characters (who are arguably more three-dimensional than the ones in the other installments), it’s the humans who take the driver’s seat. Think of it as an Edo-period samurai drama with yōkai cameos.

Sources for this article: Yokai Attack! The Japanese Monster

Survival Guide, by Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt; Yokai.com