(1997) Directed by Guillermo del Toro; Written by Guillermo

del Toro and Matthew Robbins; Based on the short story, “Mimic,” by Donald A.

Wollheim; Starring: Mira Sorvino, Jeremy Northam, Alexander Goodwin, Giancarlo

Giannini, Charles S. Dutton and Josh Brolin; Available on Blu-ray and DVD

Rating: ***½

“There was something in this movie that forced me, like the Mimics, to evolve into something different. It was perhaps not quite human, if you look at my body proportions, but certainly made me survive, and made me find my own voice and my own personality, visually…” – Guillermo del Toro (from Director’s Cut Blu-ray commentary)

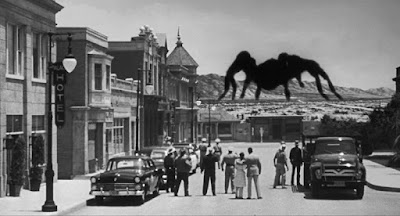

If there’s one cohesive theme throughout Bug Month, it’s

that our days as the Earth’s dominant species might be numbered. Many of us view

insects as inferior lifeforms, unworthy of our attention. It could only take a little

push to upset the balance, tipping the scales in their favor. Mimic

suggests that this day of reckoning, thanks to our hubris, could be much closer

than we think.

* Note: Above all, the most disturbing issue behind the scenes was Ms. Sorvino’s ongoing harassment by Miramax head, Harvey Weinstein.

** Note II: In a 2017 interview, del Toro commented, “My first American experience was almost my last because it was with the Weinsteins and Miramax. I have got to tell you, two horrible things happened in the late nineties, my father was kidnapped and I worked with the Weinsteins. I know which one was worse… the kidnapping made more sense; I knew what they wanted.” (excerpted from IndieWire article by Zack Sharf)

*** Fun Fact #1: At the insistence of Miramax, the original script from del Toro and Matthew Robbins was subjected to numerous re-writes by some of Hollywood’s most prominent figures, including John Sayles, Steven Soderburgh, and Matthew Greenberg.

**** Fun Fact #2: According to del Toro, much of the second-unit work (shot by Robert Rodriguez, among others), which was utilized in the theatrical cut, was removed for the “Director’s Cut.”

The opening scene establishes that New York City is besieged by Strickler’s disease (not to be confused with Stickler syndrome), a deadly epidemic that strikes children.* Dr. Susan Tyler (Mira Sorvino), a brilliant young entomologist, develops a new species of insect,** the “Judas Breed” (incorporating some DNA from cockroaches, termites and mantids), to combat the roaches that carry the contagion. Initial results are promising, but in the researcher’s zeal to solve one problem, she creates a potentially larger one. Dr. Tyler discovers that the new species, left to its own devices in the secluded lower recesses of the New York subway system, is thriving. The bugs were genetically engineered to be sterile, but to borrow a phrase from a certain popular dinosaur movie, “Life, uh…finds a way.” If left unchecked, this new life form could threaten the population of New York City and beyond.

* Fun Fact #3: The stylized opening scene (excised from the theatrical cut) became another bone of contention when the producers asserted the set didn’t resemble a real-life hospital.

** Fun Fact #4: According to del Toro, he originally wanted the Mimics to be based on the White Oak Borer Beetle, but Miramax executives (apparently associating NYC with another common insect) insisted that cockroaches should be the star of the show.

Sorvino is likeable in her lead, relaxed performance as intrepid researcher Dr. Tyler. Not quite as convincing is Jeremy Northam as her husband (and CDC official), Dr. Peter Mann, the film’s nominal hero. It’s not terribly surprising that his performance never quite gels, considering Northam wasn’t del Toro’s first choice to play the character (del Toro wanted an African American actor to play Dr. Mann, but the shortsighted producers objected to the inclusion of an interracial couple). Possibly because of the script revisions and cuts, some other characters are reduced to bit roles: F. Murray Abraham as Dr. Tyler’s mentor, Dr. Gates, and Josh Brolin as an unlucky police detective.

The most intriguing supporting character is Chuy (Alexander Goodwin), a young neurodivergent boy with uncanny powers of observation. Chuy possesses an innate talent for determining shoe size on sight and, most importantly, imitating the clicking sounds of the human-sized insects. Rather than feeling revulsion, he seems entranced by the Mimics’ odd appearance, referring to one of them as “Mr. Funny Shoes.” Unlike everyone else who has encountered them, he doesn’t display fear, which proves to be his protection. He forms a special connection with the creatures through communication, clicking spoons to mimic the Mimics.

A common theme in del Toro’s films is how he shines the spotlight on marginalized people. In Mimic, he illustrates how individuals can appear to be little more than insects to the upwardly mobile. Manny (Giancarlo Giannini),* runs a humble shoe shine business in a bustling subway station. His grandson Chuy, who possesses unique patterns of cognition and interpreting the world, seemingly exists in a world of his own. The film draws further parallels to our hierarchical society, with a group of sweat shop workers who fall prey to the Mimics. The people behind the garment manufacturer are no less predatory or unfeeling than the Mimics (one shot lingers on a label that reads “Proudly Made in the USA,” reminding us the means don’t necessarily justify the end). One of del Toro’s many talents is featuring characters you might initially write off, infusing them with nuances that make them rise above plot devices. On the surface, beat cop Leonard (Charles S. Dutton) is just another cog feeding into a bureaucracy, but he proves to be much more, versed in the rich, forgotten history of the subway system, and a snarky sense of humor (he also delivers the film’s best line).

* Fun Fact #5: Before Giannini was cast in the role of Manny, the studio considered other actors, including Ian Holm, Max von Sydow, and André Gregory. The director’s initial choice was Federico Luppi (ultimately rejected because his English was a bit shaky), who appeared in del Toro’s previous film, Cronos (1993), and subsequent production, The Devil’s Backbone (2001).

The distinctive look of the title creatures is the main

attraction. Aiming for something that appeared real, rather than fanciful, del

Toro insisted on a “National Geographic” approach, eschewing features that didn’t

already exist in the insect world.* Designed by TyRuben Ellingson and refined

by effects virtuoso Rob Bottin, the Mimics were brought to life through

puppetry effects by Rick Lazzarini.** The creature design accounted for factors

that limited the size of insects and other arthropods, incorporating lungs and

a modified exoskeleton more suited to a much larger organism. The icing on the

creepy cake is a bipedal creature that presents a crude, albeit effective

approximation of our appearance. The result is at once mesmerizing and unnerving.

* Fun Fact #6: In another battle (which del Toro thankfully won), the producers were perturbed that the Mimics looked too much like bugs, as opposed to some alien life form. They suggested adding teeth, gums and hair – none of which are present in insect anatomy.

** Fun Fact #7: Among Lazzarini’s memorable prior contributions were the Budweiser frogs, which appeared in a series of popular commercials in the ‘90s.

As with all of his films, del Toro incorporates layers of

substance into his style. Catholic iconography figures prominently throughout, signifying

the intersection of the spiritual and concrete (science-minded) worlds. The use

of color also presents a stark contrast, with vivid golds and blues, representing

the juxtaposition of the human and insect realms. In his commentary, del Toro

described another theme throughout the film, as a contrast between fecundity

(the Mimics) and infertility (Dr. Tyler’s personal struggles to conceive a

child).

Guillermo del Toro referred to his movie as an “imperfect child,” an apt description for the end product of too many chefs meddling with the recipe. In his “Director’s Cut” commentary, he takes a philosophical (and likely diplomatic) outlook to his ordeal grappling with the multiple producers. While his vision was inevitably compromised, the painful process of give and take helped map a future blueprint for his filmmaking methodology. Mimic is a film full of great ideas, memorable imagery, creatures that evoke chills, and a top-notch Marco Beltrami score. It suffers from a few too many loose ends, undeveloped characters, and an ending that’s far too pat (the original, un-filmed, ending envisioned a much darker conclusion which seemed more in line with del Toro’s sensibilities). Even if Mimic falls a bit short at times, it’s well worth a look (especially the Director’s Cut), to spot the elements del Toro would continue to refine and develop, to great effect, in his subsequent films.

Sources for this article: Director’s Cut Blu-ray commentary; Guillermo del Toro – Cabinet of Curiosities, by Guillermo del Toro and Marc Scott Zicree; “Guillermo del Toro ‘Hated the Experience’ of Working withHarvey Weinstein on ‘Mimic’,” by Zack Sharf, IndieWire