(1967) Directed by: Konstantin Ershov and Georgiy Kropachyov; Written by Konstantin Ershov, Georgiy Kropachyov and Aleksandr Ptushko; Based on the story by Nikolay Gogol; Starring: Leonid Kuravlyov, Natalya Varley, Aleksey Glazyrin, Vadim Zakharchenko and Pyotr Vesklyarov; Available on Blu-ray, DVD and Shudder

Rating: ****

“A curse upon you! With the wings of a bat! With the blood

of a serpent! I shall curse you!”

– Pannochka (Natalya Varley)

Note: The following review is an expanded version of a capsule review from December 2016.

Although fantasy and science fiction films enjoyed their

place in the former Soviet Union, the horror genre didn’t fare nearly as well. Viy

(aka: Viy or Spirit of Evil) is often touted as the “first”

Soviet-era horror film (admittedly, what does and doesn’t constitute horror is

up for debate), and in the absence of other salient examples, it’s difficult to

dispute this claim. While it’s clear that subjects of a supernatural bias were

discouraged, I’m not quite ready to accept that this was the only horror movie

to be released between 1922 and 1967. Nevertheless, evidence to the contrary has

yet to surface. Viy was based on an 1835 short story by noted Ukrainian

author Nikolai Gogol. The original novella professes to be derived from

Ukrainian folklore, but whether or not it was entirely concocted by Gogol

remains open for debate.

In the opening scene, set in a Kiev-based seminary, the

stern rector dismisses his students for a holiday break. Khoma (Leonid

Kuravlyov) and two of his fellow students promptly take to the countryside for some

fun and mischief (much to the chagrin of their schoolmaster). Before long,

tired and weary from their travels, they seek shelter at in a farmhouse owned by

a withered old woman (Nikolay Kutuzov). She reluctantly puts them up for the

night, insisting that Khoma sleep in the stable. Things take a bizarre turn

when she singles him out, hopping upon his shoulders and revealing her true

nature as a witch. After soaring over the fields, they return to earth. He

beats her with a stick, leaving her for dead, but a second glance reveals not

an old crone, but a young woman. Puzzled and disturbed, Khoma returns to the

rectory, only to learn that the headmaster has received an unusual request – he

alone must hold a three-day prayer vigil for a wealthy Cossack’s recently

deceased daughter, Pannochka. Now, Khoma and the witch are inextricably

entwined.

Leonid Kuravlyov is a hoot in his manically comic performance as our perpetually bewildered protagonist, Khoma.* Far from the most diligent student at his rectory, he’s more concerned with food, drink and revelry than spiritual enlightenment. He tries to do everything he can to weasel out of his obligation to the Cossack patriarch, but the promise of a thousand gold pieces or a thousand lashes (if he disobeys) sways his decision. Each successive day of the vigil takes its toll on Khoma, while he’s locked away in the chapel, repeating his mantra, “A Cossack is never afraid of anything.” Meanwhile, his mental and physical state continue to erode as he endeavors to keep the evil spirits at bay and contend with a corpse that refuses to remain still.

* Khoma’s tentative demeanor reminded me of another literary

character, Ichabod Crane. Although I’m not sure if Gogol was aware of

Washington Irving’s story (published in 1820), its main character could be a

spiritual predecessor.

All eyes are on Natalya Varley as the not-so-deceased, Pannochka.

With her long dark hair and pallid complexion, she resembles the Iron Curtain’s

answer to Luna (from Mark of the Vampire) or Morticia Addams. She speaks

very few lines, but makes them sting, proving, hell hath no fury like a witch

scorned. Varley takes charge in every scene she’s in, dominating the scenery with

her frenzied, hypnotic stare.

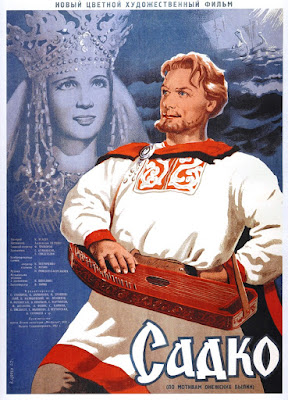

The visuals of Viy benefited greatly through the

efforts of fantasy filmmaker Aleksandr Ptushko (Sadko, Ilya Muromets),

who provided the art direction and effects. Gogol’s story was vague in the

details about Khoma’s climactic confrontation with evil. The filmmakers,

however, gleefully fill in the blanks, delivering some genuinely unnerving moments

when the forces of darkness are unleashed in the chapel. It’s a dazzling

display, brought to life through dynamic, swirling POV shots, as all manner of things

that go bump in the night descend upon poor Khoma. Demons scuttle down the

walls and skeletons dance about, culminating in the appearance of Viy, a stocky

demon with giant eyelids, concealing a gaze that can kill. The final, visually

dense sequence, is a treat for the eyes, providing more than can be taken in

with one viewing.

Viy enchants and entertains, with its tantalizing mixture of comedy and the macabre. This faithful adaptation of Gogol’s story must have been a tough sell for the staid sensibilities of the prevailing regime, but it’s a testament to the persistence of Ptushko and co-directors Konstantin Ershov and Georgiy Kropachyov that their vision made it to Soviet theaters. Whether it was truly the first horror film or not, Viy remains an important landmark in Russian cinematic history, when films of the uncanny were such a scarce commodity. Its robust imagery and themes make it a force to be reckoned with, and no discerning fan of horror should consider his or her education complete without giving this a look.