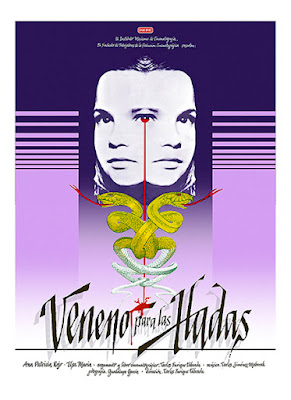

(1986) Written and directed by Carlos Enrique Taboada; Starring: Ana Patricia Rojo, Elsa María Gutiérrez, Leonor Llausás, Carmen Stein, María Santander, Ernesto Schwartz, Rocío Lazcano and Blanca Lidia Muñoz; Available on Blu-ray and DVD

Rating: ****½

“Fairies don’t get along with witches. They’re afraid of

them. The witches are their enemies and they kill them. Have you seen the

boiling pots that witches have? They throw in lizard tails, cemetery dirt,

ashes from crosses, snakes, and lots of rubbish. You know what they make?

Poison. Poison for the fairies.” – Nana (Carmen Stein)

Childhood friendships impact us at a particularly vulnerable, formative period in our lives, creating experiences that often serve as a template for future relationships. If we’re lucky, it’s a bond that lasts a lifetime, but even if that friendship only spans a short period, the memories endure. On the flipside, our early childhood bonds frequently teach us hard lessons about the sort of people we’re better off steering away from. Writer/director Carlos Enrique Taboada (hardly a household name in the States, but remembered fondly in his native Mexico)* captures the latter sentiment in his gothic thriller, Poison for the Fairies (aka: Veneno para las Hadas). Taboada’s 14th and final film** (completed in 1984 but not released until 1986), focuses on the dysfunctional relationship between two school-age girls and its awful consequences.

* Fun Fact #1: In 1957, hoping to witness a ghost, Taboada had himself chained to a tombstone in a graveyard. Whether or not he witnessed any supernatural occurrences is anyone’s guess.

** Not-So-Fun Fun Fact: Taboada shot another movie (on

video), Jirón de Niebla (aka: Shred of Mist), but due to lack of

financing was unable to edit or release the film. The footage was reportedly lost.

Flavia (Elsa María Gutiérrez, in her only film role) arrives

at an exclusive Mexican private school, where she quickly befriends Verónica (Ana

Patricia Rojo), a strange girl the other classmates appear to shun. It doesn’t

take Flavia long to learn why most of Verónica’s peers keep her at arms’ length,

with her claims about being a practicing witch. Flavia initially meets her new

friend’s proclamations with skepticism, which eventually gives way to an uneasy

acceptance. When Flavia laments having to take her piano lessons, Verónica

offers to cast a spell (with a blood oath) to make Flavia’s instructor, Madame

Rickard (Blanca Lidia Muñoz), go away. Shortly afterwards, during a practice

session, her teacher suffers a fatal stroke. Instead of regarding it as an

unfortunate coincidence (it’s revealed, in her parents’ conversation, that her teacher

had a history of illness), Flavia believes it was Verónica’s

doing. Whether there was some connection, or terrible luck, it’s all the

leverage Verónica requires to take control of Flavia’s life.

Over the course of the film, the power dynamic between the two girls shifts, which Verónica exploits to embed herself in Flavia’s life. Flavia comes from an upper-class family with loving, if somewhat detached parents. Verónica, whose parents are dead, lives with her grandmother and housekeeper, Nana (Carmen Stein). Nana, who seems to be Verónica’s primary parental figure, is fond of telling stories about witches and casting spells. In turn, Verónica takes the stories to heart, professing to Flavia that she’s not really a 10-year-old girl, but an ancient witch. The film takes an ambiguous stance about whether Verónica truly believes she’s a witch, or Nana’s supernatural tales are simply co-opted to deceive and control her impressionable friend. Verónica, envious of what she perceives to be Flavia’s idyllic existence (and using the piano teacher’s death as leverage), covets her possessions and connives to accompany her on a family vacation to their country estate. Flavia, fearing some sort of retaliation, submits to her friend’s increasingly unreasonable demands, culminating in collecting the raw materials to create a witch’s potion. Verónica’s unyielding behavior, coupled with Flavia’s belief in her friend’s powers, becomes a volatile combination, leading to a horrific conclusion.

The exceptional cinematography by veteran cinematographer Lupe

García contributes immensely to the film’s perspective, told from the children’s

point of view. García expertly captures a child’s eye view of the world,

inhabited by authority figures who dwell in the periphery. While Flavia, Verónica,

and their schoolmates remain in full view, adults are often shot in silhouette,

from behind, or from a low angle. We’re never in doubt that this is the kids’ story.

Being a witch and yielding black magic (or at least the prospect of said magic)

becomes a potent drug for Verónica, as a means of exerting power at an age when

children often think of themselves as powerless.

Poison for the Fairies is a gothic thriller that leans into horror, subverting some of the latter genre’s tropes (such as Flavia’s visions of witches) for the narrative. Carlos Enrique Taboada depicts the darker side of childhood friendship and the loss of innocence. Flavia becomes embroiled in a toxic relationship because the alternative, being alone, is unbearable. Under the guise of friendship, Verónica manipulates her to do things she otherwise wouldn’t do on her own. Flavia’s belief in her friend’s supernatural powers overshadows her sense of reason, until fiction becomes fact. With its timeless themes, intense performance by Ana Patricia Rojo (channeling The Bad Seed), and thread of ambiguity (leaving the film open to almost as many interpretations as there are filmgoers), Poison for the Fairies deserves to be experienced and appreciated by a whole new generation of filmgoers.

* Fun Fact #2: Although the film was not a box-office

success, it won the hearts of critics, earning five Ariel Awards (the Mexican

equivalent of the Academy Awards) in 1986, including Best Picture and Best

Director.

Source for this article: “Behold the Duke of Mexican Horror Cinema,” by Abraham Castillo Flores (essay in Vinegar Syndrome set, “Mexican Gothic: The Films of Carlos Enrique Taboada)