Orochi (1925) Tsumasaburô Bandô stars as Heisaburo Kuritomi, a disgraced samurai. After being castigated by his master for a fight he didn’t initiate, he’s marked as a troublemaker. His life only continues to take a downward spiral from there, after he’s eventually banished from his village. The now masterless samurai (ronin) moves to a new town, where (due to a series of misadventures and misunderstandings) he becomes the local pariah. Bandô captivates in his tragic role, as a man doomed to live a life of unrequited love and failed aspirations. Orochi reminds us that the outwardly virtuous, as well as the apparently detestable, may not be all that they seem to be. The DVD from Digital Meme’s “Talking Silents” series provides a uniquely engaging viewing experience, featuring Benshi narration, in which a host tells the story, performing the voices for each of the characters.

Rating: ****. Available on DVD

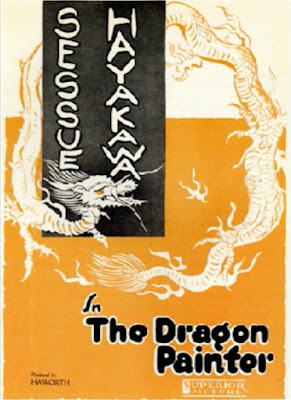

The Dragon Painter (1919) Sessue Hayakawa stars as Tatsu, a mercurial artist living a monastic existence in the mountains. All of his paintings are an interpretation of his long-lost love, a woman who was turned into a dragon 1,000 years ago. After viewing his art, an elderly painter views him as his worthy disciple. In an effort to keep the reluctant artist, he convinces Kano that his daughter Ume-Ko (Tsuru Aoki) is the woman he’s been questing all his life. As embodied by Hayakawa, The Dragon Painter (based on the novel by Mary McNeil Fenollosa) demonstrates how madness and talent frequently reside together. Much like Tatsu’s creations, it’s a simple tale, elegantly told, managing to create a nuanced character study with bold, spare strokes.

Rating: ****. Available on DVD (Out of Print)

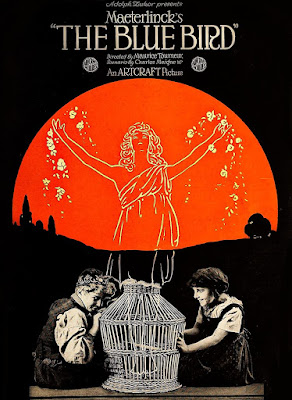

The Blue Bird (1918) This visually imaginative fantasy film from director Maurice Tourneur (the father of director Jacques Tourneur), based on a play by Maurice Maeterlinck, is a delightfully weird and wonderful feast for the eyes. Two young children, Mytyl and Tyltyl (Tula Belle and Robin Macdougall) search for the Blue Bird of Happiness, with the aid of a fairy (Lillian Cook). With the help of his magic cap, Tyltyl sees things as they truly are. Along their quest, they experience a series of whimsical (and sometimes downright creepy) adventures, finding a new appreciation for the things they already possess. While the conclusion won’t surprise anyone, it’s a fun voyage, perfect for kids, or adults who never lost touch with the kid inside.

Rating: ****. Available on DVD (Out of Print)

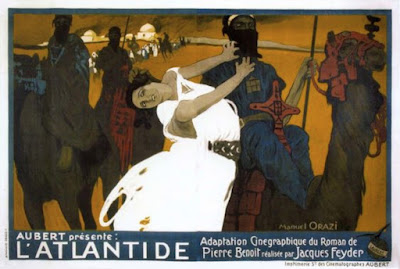

The Queen of Atlantis (aka: Missing Husbands, or L'Atlantide) (1921) French soldiers locate a missing army lieutenant (Georges Melchior) wandering alone and dying of thirst, in the Saharan desert. His companion, Captain Morhange (Jean Angelo) is nowhere to be found. Thus begins the story (told in flashback) of one man’s quest for the lost city of Atlantis. Stacia Napierkowska co-stars as the capricious Queen Antinea, a woman wielding irresistible power over men. The French/Belgian production features some impressive sets and stunning location photography, highlighting Algeria’s stark, merciless desert landscape. Arguably, the film’s nearly three-hour running time could have been cut by a third, but it remains an engrossing tale of obsession driving men to extreme behaviors.

Rating: ***½.

Available on DVD

Siren of the Tropics (1927) Josephine Baker stars (in her first feature) as Papitou, a free-spirited resident of the French Antilles. You have to wade through some annoying island native stereotypes, but Baker’s charisma shines through. A lecherous businessman (Georges Melchior) with designs on his goddaughter decides to get her fiancé out of the way, by sending him to the Antilles under the auspices of prospecting minerals. He conspires with a shady business associate to ensure that he never makes it back to France. Siren of the Tropics has something for everyone, filled with drama, action, romance, and a dash of screwball comedy (Baker’s chase scene on an ocean liner reminded me of a Buster Keaton routine). But of course, the film’s true raison d’etre is a chance to showcase Baker’s formidable dancing prowess.

Rating: ***½.

Available on DVD (Part of the Josephine

Baker Collection)

The Saphead (1920) In Buster Keaton’s first full-length feature, the comic actor plays Bertie Van Alstyne, the scatterbrained son of a tycoon (William H. Crane). Bertie risks being cut off from his inheritance unless he finds a way to become a productive member of society. Can Bertie win the respect of his doubting father, and prove his merit to his sweetheart? Keaton wasn’t a headliner in The Saphead, and it shows, with the film lacking the elaborate pratfalls of his later features. It’s not without its charms, however, especially when Keaton’s singular comic genius is allowed to shine through. Unfortunately, the movie is bogged down by the other peripheral characters, and a plot that focuses on stock trading, so watch accordingly.

Rating: ***.

Available on DVD

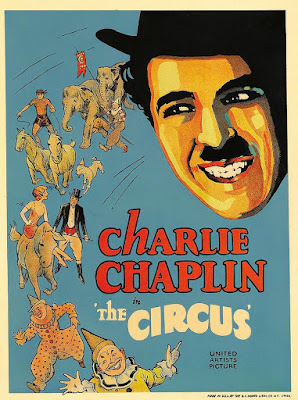

The Circus (1928) Charlie Chaplin returns for more hijinks with his Little Tramp character. After a misunderstanding with local law enforcement, he stumbles into a circus, mid-performance. His accidental routine becomes a surprise hit with the audience, and he becomes the unwitting star of the show. The film isn’t one of Chaplin’s best, but it has some inspired moments, including one scene where he’s supposed to mimic the gags of a troupe of clowns, only to end up undermining their act. He befriends a young trapeze artist (Merna Kennedy), who lives with her abusive ringmaster stepfather (Al Ernest Garcia). Kennedy and Chaplin’s chemistry seems more perfunctory than genuine, and her character’s dysfunctional relationship with her stepfather never achieves a satisfactory resolution. Nevertheless, there are some nice comic moments peppered throughout, which provide more than enough for me to give The Circus a recommendation.

Rating: ***. Available on Blu-ray and DVD