(1987) Directed by René Laloux;

Written by René Laloux and Roland Topor; Based on the novel Les Hommes Machine

Contre Gandhar, by Jean-Pierre Andrevon; Starring: Pierre-Marie Escourrou, Catherine

Chevallier, Georges Wilson and Anny Duperey; Available on DVD (Region 2)

Rating: ****

“What do you know of time, of its continuity, its traps, its false perspectives, its apparent paradoxes, its relation to space?” – Métamorphe (Georges Wilson)

When animator René Laloux burst onto the scene with his pioneering

animated science fiction film Fantastic Planet (aka: La Planète Sauvage),

it should have been his ticket to creating more stunning works. Instead, his career

could best be described as fits and starts, as he created only two other full-length

movies, Les Maîtres du Temps (aka: Time Masters), and today’s film.

Gandahar (the American version, Light Years, featured a

screenplay by Isaac Asimov)* may not be a direct sequel to Fantastic Planet, but

could easily reside in the same universe. Much like his earlier film, Laloux has

populated his alien world with a diverse array of unusual creatures and odd

landscapes, accompanied by a fittingly mind-bending story.

* Fun Fact: For Gandahar’s animation, Laloux utilized S.E.K. (Scientific Educational Korea) studios, located in Pyongyang, North Korea. Over the years, S.E.K. has been involved with numerous international productions, including several high-profile American animated TV shows and films.

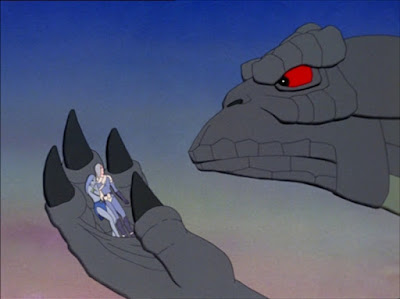

The film is set on the utopian world of Gandahar, where the residents live a peaceful existence, free of war or other ills of society. Civilization falls into disarray after the residents of Gandahar suffer an attack from an unknown source. Sylvain, an inexperienced young soldier, is sent to investigate the disturbance, and in the course of his journey, encounters a formidable robot army. Although he becomes a prisoner of the robots, he manages to escape with a fellow Gandaharian, Airelle. They fall in love, but duty calls, as Sylvain learns his true destiny – in order to save the present, he must travel 1,000 years into the future.

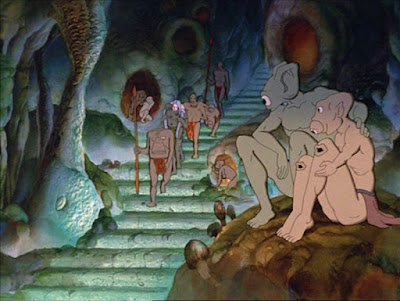

In Sylvain’s travels, he encounters a race of outcasts known

as the Deformed. According to their unique perception of time, woven into their

language (instead of saying something “is,” it’s “was will be”), they discuss

events in the past and future, rather than the present. When Sylvain asks their

leader for clarification (“Past in future, and future in past?”), he replies, “We

don’t understand it any better than you, but it has become our nature, and the

past-future has become our way of speaking and believing.” While their concept

of time may seem superficially alien, it’s relevant to many of us who fear living

in the present. We often lament what has passed and spend an inordinate amount

of thought, anticipating what may be. The Deformed, Sylvain’s presumed enemies,

become his ally in the fight against the robot invaders.

It’s not too much of a stretch to speculate that Laloux, who

grew up during the Nazi occupation of France in World War II, would likely

incorporate anti-fascist themes into his work. The totalitarian robot regime, with

its mindless battalions, pledge their unquestioning fealty to their leader, the

giant brain/demigod Métamorphe (“The Great Procreator”). They wage war against

the easy-going residents of Gandahar and their individuality, in favor of a society

based on subservience. In the future Gandahar, humans are

harnessed for their power and discarded into a heap after they’ve outlived their

usefulness – a sobering parallel to the real-life horrors of the concentration

camps.

Gandahar doesn’t fall into the trap of some science

fiction films, with lengthy passages of expository dialogue that stall the plot.

Instead, Laloux counts on the viewer to take in the sights and connect the

dots. The human residents of Gandahar once originated from Earth, and countless

ages later, still remember the stories and poems from that distant planet. They

established a better life, but there’s a trade-off for their idyllic society.

The Deformed were, in their words, “the victims of your research in the field

of genetics.” Similar to Frankenstein’s creation, they were shunned by their

creators and forced into exile. The film embraces the Frankenstein metaphor a

step further with Gandahar’s enemy Métamorphe, an artificial consciousness that

originated as a science experiment.

Compared to the more experimental look of Fantastic Planet (incorporating a distinctive cross-hatch art style, and employing a hybrid of cell animation with paper cutouts), Gandhar falls back on more conventional animation methods. There’s also some obvious cost cutting measures, with duplicated shots (depicting the robots marching). While Gandahar doesn’t break new ground, artistically, it more than compensates with its fanciful, immersive depictions of an alien world, and pastel-colored palette. Along with its eye-pleasing visuals, it presents a thought-provoking story that challenges viewers to reach their own conclusions. Unfortunately, it’s not particularly easy to come by the DVD of the French version (an excellent copy was released by Eureka in 2007), but it’s well worth seeking out.

Source for this article:

René Laloux, The Man Who Made 'La Planète Sauvage' ('The Fantastic

Planet'), by Philippe Moins, Animation World Network.

Great review, Barry!

ReplyDeleteI've enjoyed fantastic planet over the years, so I'm sure I would enjoy this one too.

Thanks so much, John! It has the same trippy vibe as Fantastic Planet, so I'm sure you'd dig this as well. Now, if they'd just release it on DVD in the States...

DeleteI am just learning about this film for the first time. It seems Avatar and the Matrix borrowed heavily from this. “The secret to genius is hiding your sources” AE

ReplyDeleteI wouldn't be surprised if this provided some inspiration for both films (and many others). Such a fascinating film.

Delete