(1927) Directed by: Fritz Lang; Written by Thea von Harbou; Based

on the novel by Thea von Harbou; Starring: Brigitte Helm, Alfred Abel, Gustav

Fröhlich, Rudolf Klein-Rogge and Theodor Loos and Heinrich George; Available on

Blu-ray, DVD and Netflix Streaming

Rating: *****

“The mediator between

head and hands must be the heart!” – Epigram

“What if one day

those in the depths rise up against you?” – Freder (Gustav Fröhlich)

From a modern perspective, it’s difficult to fathom that one

of the best known and well-esteemed films from the silent age wasn’t always regarded

as anything special. Based on Thea von Harbou’s novel and directed by Fritz

Lang, shooting for Metropolis began

in May 1925, and ran until October 1926. With a production cost of 6 million

marks (approximately $24 million in 1927 dollars),

it was the most expensive German film to date. The lavish production didn’t

translate to universal praise, however. The initial release received a lukewarm

critical reception and tepid box office. Time wasn’t kind with subsequent

releases, as the original running time of 153 minutes was whittled down to

approximately 90 minutes. Over the past 15 years or so, film preservationists

have labored to restore the film to its former glory. The most recent version,

at 145 minutes, incorporates footage from a scratchy 16 mm print from Argentina,

and is probably the most complete version we’re liable to see.

Everything about Metropolis,

ranging from the set design to the soaring cityscape to the archetypal

characters, is told in broad strokes. It’s a modern fable, rich in allegory,

with many themes that still appear contemporary nearly 90 years later. Alfred

Abel is exceptional as the cold, impassive Joh Fredersen, master of all he

surveys. He supervised the construction of the city-state of Metropolis, and

stands as its de facto ruler. He impassively observes society from atop his New

Tower of Babel, and endeavors to preserve the status quo. The laborers who make

the lifestyle for the upper class possible toil away in the subterranean city

under the city, little more than a mean to Joh’s predetermined end. Lang contrasts

the cold machine world beneath with the Club of the Sons and Eternal Gardens

above, where the wealthy come to play.

Joh’s son Freder (Gustav Fröhlich) doesn’t share his

father’s dispassionate views. He becomes determine to learn more about the

subterranean city after he’s smitten by the virginal Maria (Brigitte Helm), who

takes a group of children from the lower levels to catch a fleeting glimpse of

the Eternal Gardens. Maria has steadily gained a loyal following with her

peaceful protests. In a reversal of fortune plot similar to The Prince and the Pauper, Freder trades

places with Worker 11811 (Erwin Biswanger), and takes up his mindless job. In

one of the film’s many memorable sequences, Freder works a grueling 10-hour

shift, moving the hands of a clock-like mechanism with indeterminate purpose. While

Freder poses as Worker 11811, the emancipated laborer enjoys his brief

flirtation with luxury, riding in a limousine and attending the Yoshiwara

nightclub.

When Joh learns of his son’s sudden fascination with the

plight of the working class, he works to discredit Maria. Joh employs the

inventor Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) to endow his robot with Maria’s likeness

(also played by Helm) and set her up as a false prophet. Rotwang, however, has

ulterior motives, which are made clear in the longer cut of the film. Her robot

counterpart becomes the antithesis of Maria, a stark contrast between the

sacred and profane. She performs an erotic dance at a club, and her volatile

speech sparks a violent workers’ rebellion.

Many of the criticisms heaped against Metropolis were not dissimilar to those of modern blockbusters,

alleging spectacle over story. One of its most notable detractors, H.G. Wells,

excoriated the film* for what he deemed to be a simplistic tone and dated view

of society. It’s ironic to note that Wells’ cinematic take on utopia, Things to Come, premiered almost a

decade later, and appears to have aged less gracefully. On the other hand, Metropolis has endured, thanks to its

more metaphorical rather than literal approach. While Wells’ film differed from

Metropolis thematically, he failed to acknowledge how the earlier film shaped

many of the visual elements, including scenes of machinery and industrial might,

towering structures, elevated walkways, and communication via 2-way video screens.

Unlike Things to Come, which was

concerned with envisioning a sort of future history, Metropolis works on our subconscious, projecting human frailties,

hopes, dreams and fears within a dehumanizing society. While Wells opined the

rational side would prevail, von Harbou argued this was not enough. There had

to be a mediator between the forces of rationality and brute strength. Although

the future world of Metropolis is

fantastical, it seems less sterile than the one Wells envisioned. The old

co-exists with the new (witness how Rotwang’s machine man is brought to life

through a combination of technological know-how and alchemy), and a gothic

cathedral stands among futuristic architecture.

* According to Wells: “It gives in one eddying concentration

almost every possible foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about

mechanical progress and progress in general served up with a sauce of

sentimentality that is all its own.” (New York Times, April 17, 1927)

One of the rewards of subsequent viewings is spotting the myriad

influences of Metropolis on many other

films. The comparisons are too numerous to mention in any one article. I could

probably devote an entire essay comparing Star

Wars to Lang’s film. The eccentric inventor Rotwang and his artificial hand

could have easily been the inspiration for Darth Vader. Likewise, his

mechanical man is often cited as the template for C-3PO. Rotwang’s appearance

also bears a strong resemblance to Doc Brown in the Back to the Future Movies. The vast cityscape has been emulated

many times, from Blade Runner to Dark City to Akira. It also likely influenced Terry Gilliam’s retro-future aesthetic

for Brazil and 12 Monkeys. Gottfried Huppertz’s score, with its rousing

multi-layered themes has doubtlessly influenced other composers of epic films.

It seems as if everyone and his/her dog has reviewed Metropolis by now, but I propose every

fan (and detractor) should take a crack at re-evaluating the film. No, this isn’t

a perfect movie – the acting is suitably over the top, particularly by Fröhlich,

whose portrayal of Freder appears hopelessly naïve. Subtlety is not Lang’s

strong point, but the subject matter requires a broader palette. The anachronisms

are a stylistic flourish, not meant to be a realistic representation of future

society. The iconic imagery, thanks to cinematographers Karl Freund, Günther

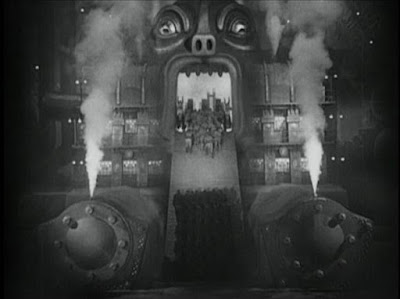

Rittau and Walter Ruttmann is steeped in metaphor (One of the most iconic

images involves workers marching up to the M-Machine, sacrificial offerings to

feed the machinery’s insatiable appetite). A film isn’t classic because everything

makes sense, or it’s uniformly liked by everyone. The sign of a great classic

is that it transcends the time in which it was conceived, demanding repeated

viewings. Metropolis’ influence has

spanned decades, and will continue to spawn debate and imitation for many years

to come.

Excellent review, Barry! The Rotwang/Doc Brown comparison was new to me, but I totally see it.

ReplyDeleteThank you, John! I'm glad you see the connection too. I was wondering if I was crazy for thinking that... or is it a shared psychosis? :)

DeleteGreat review, I agree that it should be considered a classic and was lucky to view this on the big screen. I like it but for a first time watch I would reccomend the 1984 Giorgio Moroder cut which adds in a lot of 80's pop music at the time. It has a lot of symbolism and it's references are clear

ReplyDeleteThanks, Vern! I'm envious that you were able to catch this on the big screen, and I agree that I need to check out the Giorgio Moroder version. I've shied away from it for far too long, which is odd, being a product of '80s pop culture.

ReplyDelete